Pop Culture Posts

In reviewing the original Star Trek series (1966-69), for critical themes, there are a number of lenses which can be applied such as ideology, gender and race.

Stack and Kelly (2006) in their article, “Popular Media, Education, and Resistance,” talk about the influence of popular media and how it can provide a place outside of education for individuals to be exposed to resistive non-dominant representations. This can be in the form of different representations of age, race, class, ability, religion, gender, sexual orientation or ideology. (p. 9) The original Star Trek, and subsequent series had the opportunity to fulfill this purpose by influencing legions of “Trekkie” fans with its’ humanistic messages throughout the decades.

Bernardi (1997) states that NBC had objections to the portrayals of characters, “… including Number One Majel Barrett), a strong woman character who was the ship’s second-in-command,” because they felt the character wouldn’t be accepted by the television audience. This illustrates that at that time many viewed women as having a subordinate position in society. (p. 215)

This exemplifies Stack and Kelly’s (2006) argument, “The media are a pivotal vehicle through which the social is continually recreated, maintained, and sometimes challenged” (pg. 9).

Star Trek had the capability to “share and disseminate viewpoints alternative to dominant narratives” (Stack & Kelly, 2006, p.9). As a network TV show, it could reach thousands of people and it had the potential to influence a new way of thinking that went against societal norms at that time, and to encourage change, particularly when it came to race and gender roles. Creator Gene Roddenberry’s liberalist-humanist views intended to present a Utopian future society where issues of racism, gender equality and war would no longer exist. But at the same time representations worked to undermine that ideal.

Roddenberry wanted, “to develop a show that was intellectually stimulating and addressed social issues.” (Johnson 2005, p.72). However, there is a contradiction between representations and narratives: although this is supposed to be a utopian society without those issues, in reality the show presents a world which is male dominated, where women are portrayed largely as sex objects and although racism doesn’t seem to exist among humans, there is still racism between species such as humans, Romulins and Klingons. The counter narrative is that in the “real world” during the time period of the show (late 1960’s), racism still existed in society. It was a divisive issue with strong opinions on both sides. In addition, the network wielded power over the show, at times overriding Roddenberry’s idealistic views which they sometimes saw as controversial.

In the episode, “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” a narrative of anti-racism is conveyed. The Enterprise picks up the last two survivors of a war-torn planet who are still intent on destroying each other. The half-black, half-white aliens hate each other because they are oppositely coloured. The two continue to escalate fighting until the Enterprise reaches their home planet, only to find that the planet has been destroyed due to intense racial hatred. Instead of learning from the tragedy, the two begin to blame each other for the planet’s destruction and continue to fight. Critics viewed this representation of racism as being heavy-handed, although fans of the show felt it was one of the best episodes due to its message.

On the one hand, the series provided social commentary of anti-racism (see above) or presenting “the United Federation of Planets.” At that time television was dominated by the depiction of white people and Star Trek went against that by including multi-racial characters such as Uhura and Sulu. The counter narrative to this is that they are portrayed as non-essential and in the background, compared to white male hero, Captain Kirk.

Bernardi (1997) states:

Contrary to what is commonly said about this science fiction series, … Star Trek’s liberal-humanist is exceedingly inconsistent and at times disturbingly contradictory, often participating in and facilitating racist practice in attempting to imagine what Gene Roddenberry called, “infinite diversity in infinite combinations. (p. 211)

In relation to ideology, through creation of a complete universe with its own morals, technology and culture, science fiction texts such as this are more likely to be viewed as realist texts.

Therefore, with such a close relationship to realism, the writers of Star Trek could infiltrate contemporary concerns of its production time, such as civil rights and the Cold War, into its diegesis (Gregory 2000, p.25; Bernardi 1997, p.214)

In conclusion, although creator Gene Roddenberry’s intention was to create a cerebral show with the potential to influence social change, some of the representations were in fact counter narratives to that.

References:

Bernardi, D. (1997) Star Trek in the 1960s: Liberal-Humanism and the Production of Race in Science Fiction Studies , 24 (2): 209-225.

Gregory, C. (2000) Star Trek: Parallel Narratives. New York: St. Martin’s Press. (p. 25)

Johnson, C. (2005) Telefantasy. London: British Film Institute Publishing. (p. 72)

Stack, M., & Kelley, D.M. (2006) Popular media, education and resistance. . Popular media, education, and resistance. Canadian Journal of Education , 29(1), 5-26.

Disney Princess: Enchanted Journey is a video game of the Disney Princess franchise, which was released for the Wii in 2007. Targeted at kindergarten-aged girls, the game centers on a girl whose quest is to help restore a run-down castle by helping five princesses —Snow White from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Ariel (The Little Mermaid), Belle from Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin’s Jasmine, and Cinderella in their struggle against an evil witch and her “Bogs.”

At first glance this game has a feminist narrative in that in contrast to the Disney Princess story lines, the various Princesses are not rescued by princes; they go on their own adventures and move through various stories, responsible for their own accomplishments. The counter narrative is that the Princesses are represented as being pretty, concerned with appearance and goal-oriented towards “decorating and making the castle beautiful,” or adorning themselves with beautiful dresses and jewels. This positions females as being inferior to males, concerned with superficial things such as clothing and décor, versus more substantial accomplishments. Their power is the use of a magic wand, which infers they do not have real power and their accomplishments are not as a result of intelligence or skill, but something beyond their control. They turn “Bogs” (evil minions) into butterflies, rather than fighting or killing them, which would be a typical action in a male-oriented game. After progressing through levels which involve five Disney Princesses, the final battle is against Zara – an evil ex-Princess whose goal is to “stop every girl from becoming a Princess.” Looking at this from the perspective of a feminist lense I have to ask, “Is this the highest goal a girl can strive for?”

This game (and related merchandise), anticipates girls’ identities and embodies social roles for them as being lesser than boys, by having them “flick a magic wand” to solve problems, rather than using reason, and immersing them in the idea that appearance is everything. The Disney Princess product line influence girls to undertake a discourse of expected roles and behaviour with limited potential and significant social limitations. According to Wohlwend (2008), this happens through modelling of:

“particular ways of talking, speaking, dressing, playing, and so on, that index affiliation with a larger group or set of beliefs. Because these ways simultaneously index a group’s beliefs and tacit rules, I also use discourse in a Foucauldian sense to indicate how language circulates power in global and local ways…, (p.58)

So while girls may wish to overcome social limitations and predetermined gender roles, they are also torn to re-enact the story lines and behaviour they are bombarded with on many levels. The invasive nature of the media and in particular, marketing have a subliminal effect on gender roles and the self-image of girls:Steyer and Guggenheim (2017) state that:

“Decades of research, outlined in this report, demonstrate the power of media to shape

how children learn about gender, including how boys and girls look, think, and behave.

Depictions of gender roles in the media affect kids at all stages of their development,

from preschool all the way through high school and beyond. These media messages

shape our children’s sense of self, of their and others’ value, of how relationships should

work, and of career aspirations.

Tragically, that influence has served to perpetuate notions that boys have more value

than girls. Gender stereotypes riddle our movies, TV shows, online videos, games, and

more, telling our boys that it’s OK to use aggression to solve problems and our girls that

their self-worth is tied to their appearance. These images are so deeply ingrained and

pervasive that many of us don’t even notice the bias, making it more insidious because

we don’t even realize we’re exposing our children to it.” (Introduction)

Here is an advertising trailer for the game:

Trailer Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEVVXsHHCIA

In terms of a critical lense, it would appear that this game is geared towards girls: only girls appear in the advertising materials, playing the game and having “fun.” The text displayed in the commercial reads, “Enter a World of Magic Where Dreams Come True.” “Create and Dress Up Your Character” and “Awaken the Princess in You.” The key message is clear, “It’s fun to be a Princess!” The marketing materials feature images of the princesses in their fancy gowns and many of the associated products for sale in store are available in pink and/or purple, traditionally “female” colours.

This game ties in to Disney marketing through merchandise sales of a variety of Princess items including costumes, clothing, school supplies, CDs and DVDs. These items are sold through a variety of product lines including “Disney Princesses” (all five together), and each individual Princess which can appeal to a variety of girls due to their different hair colour. Jasmine is the only Princess who represents a non-white ethnicity, which when viewed with a cultural lense skews this product in its emphasis of the portrayal of Caucasians as a beauty ideal. Many young girls aspire to the looks, dress and behavior of these princesses, seeing them as an ideal in beauty and behaviour.

Buckingham (2011) writes, “According to Bauman, consumption has now become central to people’s lives; it is the condition of their identity, their very reason for being. The power of consumerism is inescapeable and all encompassing…” (p. 29)

The pervasiveness of the stereotypical Disney Princess discourses perpetuated by consumerism can create limiting social expectations for girls. Since young girls may be exposed to this game and other Disney Princess discourses, they may grow up upholding a subservient gender role to boys. This can influence their behaviour in social situations, unless this is challenged by those around them, or they themselves learn to use a critical lense, ultimately transforming their gender and societal roles.

References:

K. Wohlwend (2008) Damsels in Discourse: Girls Consuming and Producing Identity Texts Through Disney Princess Play

Indiana University, Bloomington, USA

Retrieved from: http://www.seriousplaylab.com/pop/princess_play.pdf

James P. Steyer and Amy Gugeinheim Shekan (2017)

Watching Gender: How Stereotypes in Movies and on TV Impact Kids’ Development

Retrieved from: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/pdfs/2017_commonsense_watchinggender_executivesummary_0620_1.pdf

Buckingham, D. (2011) Understanding Consumption in The Material Child: Growing up in Consumer Culture.. London: Polity Press.

This story begins in the traditional way and morphs in a new direction, and in fact becomes a completely new and different story. Rather than blowing down the house of straw, when the wolf huffs and puffs he blows the first pig out of the story. This lets the reader know this is not the “traditional” telling of the Three Little Pigs Story and makes them wonder what will happen next.

The pigs find their way out of the story to a new world and meet other fairy tale characters such as the Cat from Hey Diddle, Diddle and a dragon. They go on adventures in other stories/worlds and end up with a happy ending, back in their home. The author’s use of a nonlinear format makes the book more interactive for the reader because they are unsure what will happen next. The story can and does go anywhere. There are a variety of visual techniques employed narratively such as speech bubbles, seeing the pig both inside and outside the story on the same page, and even drawing the pigs in a cartoonish style while inside the story, but in a realistic way while outside the story. These types of representation give the reader context as to when the pig is real, or in the storyline.

One thing I found interesting is that the reader has to interpret the pictures in order to notice the transformations because the text doesn’t always tell us what is going on. The reader needs to go back and look at the illustrations carefully, multiple times to understand the full meaning of the story because each time you may notice different things. The connection between this version of The Three Little Pigs and critical literacy is that we as readers need to analyze this text closely in order to understand both implied or underlying meanings as well as obvious ones. There can be more than one interpretation and critical thinking skills are required, rather than just basic decoding.

The author uses multiple perspectives in the story: the wolf, the pigs and the reader. In terms of representation, initially in the story the wolf is represented as being threatening to the pig (as shown through the wolf’s facial expression while knocking on the door, and the pig’s look of fear). When the wolf tried to blow the house in and he blew the pig right out of the story, the next page shows the wolf’s look of disbelief as he looks around for the pig who has disappeared (despite the fact the text on that page reads, “and ate the pig up.”). Simultaneously, the pig is shown as being “outside the page” and drawn in a realistic way (versus the cartoon wolf), with the thought bubble, “Hey! He blew me right out of the story!” Suddenly, the balance of power has shifted.

When the wolf tries to blow down the house of sticks we see the first pig insert himself from outside the story, (literally from white space outside the picture), and invite the second pig, “Come on, it’s safe out here!” The pigs throw the whole narrative up in the air by messing up pages, and making a paper airplane to escape. The author, again playing with narrative, breaks the fourth wall by having one of the pigs look out of the book at us exclaiming, “Hey! I think someone’s out there!”

This post-modern version of the Three Little Pigs serves not only as a story, but also allows us to consider the nature of story. When we first begin reading, we may have a preconceived notion of what is going to happen, but that quickly changes when the pig flies away on a paper airplane out of the story. The author also uses text to keep the reader’s attention such as when one of the pigs crash lands and says, “wait—-what’s that?,” making the reader wonder what the pig sees, and what will happen next.

This story an be considered Metafiction because the author uses narrative technique to highlight the fact it is imaginary and to pose philosophical questions about the nature of reality versus fiction. This version of the The Three Little Pigs can be considered to have elements of a Post-Modern story because it employs parody (of the original Three Little Pigs story) and fragmentation (jumps from one “story” to another).

This version of The Three Little Pigs offers students the opportunity to think about the author’s purpose, study multiple viewpoints and spot gaps in the text. By comparing this version of the story with the traditional one they are familiar with, students learn that there can be different versions of a story and multiple viewpoints to think about when they are reading.

In terms of connection to critical literacy and education, while reading a “pop culture” story, students can learn to closely analyze the text on multiple levels for meaning, “the ability to not only read and write but to assess texts in order to understand the relationships between power and domination that underlie and inform them.” (Hull, 1993), (Morrell 2007).

As stated by Alvermann (2011), “…implications for classroom practice… point to the importance of creating ‘an awareness of how, why, and in whose interests particular texts might work.’ (Luke and Freebody, 1997, p. 218). Instructional frameworks for building such awareness include taking on alternative reading positions (Damico, 2005; Green, 1988) as well as achieving competence in the roles of code breaker, meaning maker, text user, and text analyst (Luke, Freebody, & Land, 2000).” (p.30)

This postmodern version of The Three Little Pigs allows them to do this. Of particular note, due to the unusual structure of this story and the variety of techniques the author employs, this story makes it easier for students to study differences, rather than simply decoding, because it is not just “your typical version” of The Three Little Pigs.

According to Morrell (2007), students also learn that society’s stories can be changed:

“Critical literacy can also illuminate the power relationships in society and teach those who are critically literate to participate in and use literacy to change dominant power structures to liberate those who are oppressed by them (Freire and Macedon, 1987).” (p. 241)

Even if in this case the society members whose power changes are pigs!

References:

Alvermann, D. E. (2011). Popular culture and literacy practices: Traditional and New Literacies. In M. L. Kamil, P. D. Pearson, E. B. Moje, & P. P. Afflerbach (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research : Volume IV, pp. 541-560. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. (pg. 30)

Morell. E. (2007). Critical Literacy and Popular Culture in Urban Education: Toward a Pedagogy of Access and Dissent. (pg 241)

In exploring issues of representation and resistance in society and media culture I will present an analysis of the cultural phenomenon of Barbie and the surrounding media influences on gender.

According to Stack and Kelley (2006), kids spend more time with media than another other institution, including school. Advertisers spend billions of dollars every year on advertising targeting children by age and sex. They have even gone so far as to create or promote characters to sell products such as Barbie animated movies (Stack and Kelley 206). Due to this pervasive influence of media it is crucial that children learn media literacy so they can develop critical thinking skills.

One of the benefits of postcolonial perspectives is that it helps students see things through a variety of lenses. As stated by Tyson (Appleman 2009), “postcolonial criticism helps us see connections among all the domains of our experience - the psychological, ideological, social, political, intellectual, and aesthetic - in ways that show us just how inseparable these categories are in our lived experiences of ourselves and our world.” (p. 87)

In order to understand the values of democracy, advantage and adversity we need education to move beyond Western stereotypes and bias. A post-colonialist lense allows diversity of opinion and promotes reflection upon our own cultural knowledge. Through this lense we are able to reframe the social practices of everyday life and create social change.

Tyson (Appleman 2009) spoke of, the “Construction of a world view that inherently privileges the perspective of those who constructed it.” In Western society, this historically has been white upper-class men. With respect to Barbie, this could have included advertising or corporate executives who made decisions about the advertising messages and imbued them with their own bias and belief systems.

According to Law and Mind (2017) , “Barbie commercials provide explicit messages to young children about the expectations associated with being female. Rather than empowering young girls to be ambitious, empowered, and virtuous, the commercials emphasize the importance of sex appeal, fashion, and relationships. “ (3)

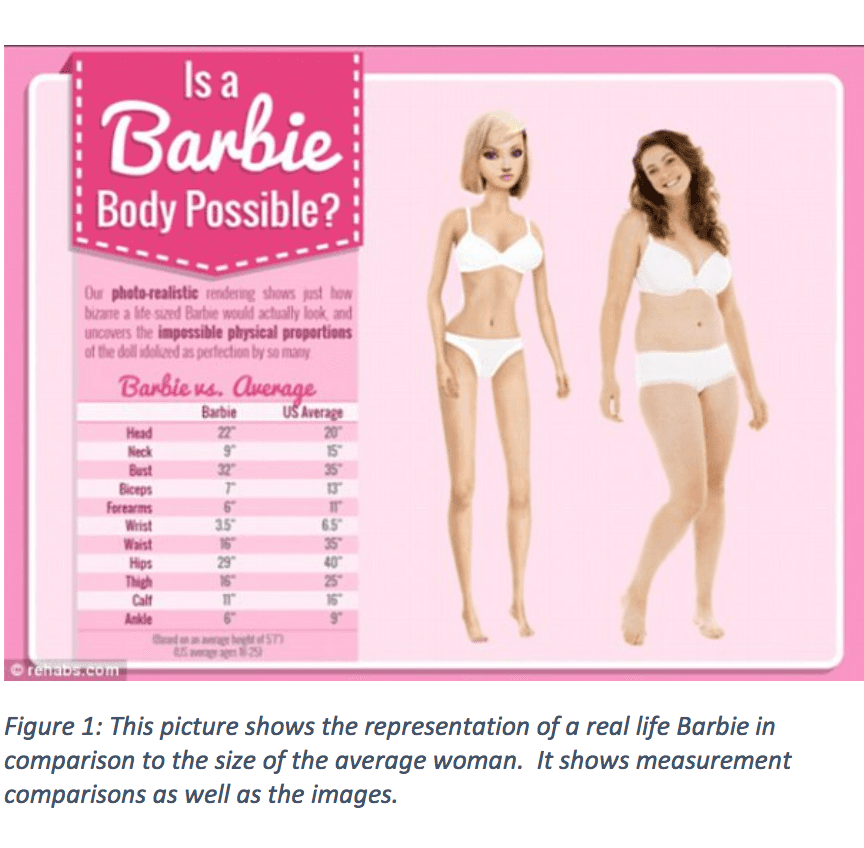

Barbie represents unattainable standards for girls for an unrealistic life with a “dream house,” “dream car,” “dream boyfriend,” ultimately leading to poor self-esteem in women who cannot keep up with this unrealistic existence.

Barbie’s body is unrealistically thin and has a tiny waist and large breasts, reinforcing the objectification of women’s bodies – and the idea that it is acceptable for women’s bodies to be judged and sexualized.

By applying a feminist lense we can observe that Barbie is portrayed as being continually happy, teaching girls they should internalize feelings of anger or sadness. Through critical analysis of the lense of gender roles we can see that she is subservient in her gender roles with Ken and focuses on her relationships with Ken, her sister and friends, teaching girls to role play about relationships, rather than focusing on education and career.

There has been a shift over time from Barbie’s role as a home maker towards fashion, materialism and sexuality. Rather than encouraging girls to control their own destiny, this encourages girls to use looks and clothing as sources of power, objectifying them, rather than empowering them. It is ironic that Barbie, with her many “career options” was supposed to be a progressive alternative to “playing Mom” with dolls. Instead, Barbie became an imposed representation of a passive female, objectified for her looks while simultaneously making girls feel inferior to her for her “dream life.”

As an educator, I would provide students with a feminist lense and ask them to consider, “Does Barbie have a perfect life? What message does Barbie send to girls (and boys) about their role in society?” In this way, themes of oppression and marginalization could be more visible.

References:

- Stack, M., & Kelley, D.M. (2006) . Popular media, education, and resistance. Canadian Journal of Education , 29(1), 5-26.

- Appleman, D. (2009). Critical Encounters in The English Classroom. Teachers College Press. Chapter: Post-Colonial Theory in the English Classroom

3. Law and Mind – Retrieved from:

As educators, we have the opportunity to utilize popular culture in our New Literacies studies in order to enhance learning and maximize creativity. I believe that this can be an important tool to enhance learning, because it provides students with the opportunity to use critical thinking to analyze text and conceive their own interpretation.

According to Hall, the production-consumption process is dialogical in nature; that is, popular culture texts are neither inscribed with meaning guaranteed once and for all to reflect a producer’s (author’s, film director’s) intentions, nor are they owned solely by creative and subversive audiences. Instead, production-in-use posits that producers and consumers of popular culture texts are in constant tension with each other. It is this tension between forces of containment and resistance, Hall argued, that theoretically enables audiences to express meaning differently within different contexts at different points in time. (p. 3)

People participate more actively and are more engaged with popular culture than traditional literacy such as textbooks because it brings together people with common skills and interests and allow them not only to watch/read/listen to culture, but also be an active participant by contributing their own content, attaining new knowledge and honing skills. In contrast to traditional education, new literacies afford more creativity or innovation, and may be less conservative, allowing students more freedom to pursue individual interests and thus become more engaged.

In my view, New Literacies consist of a mixture of cultural know-how, communication and social skills communicated across a wide range of mediums.

New Literacy Studies involve building on traditional literacy which consists largely of reading, research skills and critical thinking, shifting from the individual (or autonomous model), to participation as part of a community. It allows students to express what they like or what they think in new and different ways. Multi-literacies allow students to take a way of communicating in their daily life and bring it into their classroom, allowing them to relate the two.

Examples of compelling opportunities to utilize popular culture in a New Literacies approach to socially-contextualized learning could include: Having students chose a song that would act as a soundtrack to a scene from a film or a book and discussing the lyrics and why they chose it to represent that scene. Or, asking students to remix music or video and create their own new composition with an alternate meaning which they articulate.

One of the debates mentioned in the reading is the question of transfer. This refers to Alvermann’s idea (2011) that, “Whether or not young people’s participation in reading, viewing, listening to, and creating popular culture texts (especially digital texts) is an educational experience that has potential for transfer from informal to formal learning environments…” (p. 9). Some believe that the type of learning that takes place in the different contexts (formal vs. informal) is qualitatively different and requires bridging. However, according to Alvermann (2011), research has shown that the two types of learning can co-exist, rather than contradicting one another. It is important to note that in order for this model to work it is necessary for teachers to be supportive of students using popular culture texts in their classrooms.

In conclusion, the use of popular culture texts encourages students to make connections to society while allowing students to not only construct personal identities, but also express them. I plan to utilize popular culture in my classroom study of New Literacies as a way to enrich learning and better understand my students.

References:

Alvermann, D. E. (2011). Popular culture and literacy practices. In M. L. Kamil, P. D. Pearson,

E. B. Moje, & P. P. Afflerbach (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research: Volume IV, pp. 541-560. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.]

In reviewing the original Star Trek series (1966-69), for critical themes, there are a number of lenses which can be applied such as ideology, gender and race.

Stack and Kelly (2006) in their article, “Popular Media, Education, and Resistance,” talk about the influence of popular media and how it can provide a place outside of education for individuals to be exposed to resistive non-dominant representations. This can be in the form of different representations of age, race, class, ability, religion, gender, sexual orientation or ideology. (p. 9) The original Star Trek, and subsequent series had the opportunity to fulfill this purpose by influencing legions of “Trekkie” fans with its’ humanistic messages throughout the decades.

Bernardi (1997) states that NBC had objections to the portrayals of characters, “… including Number One Majel Barrett), a strong woman character who was the ship’s second-in-command,” because they felt the character wouldn’t be accepted by the television audience. This illustrates that at that time many viewed women as having a subordinate position in society. (p. 215)

This exemplifies Stack and Kelly’s (2006) argument, “The media are a pivotal vehicle through which the social is continually recreated, maintained, and sometimes challenged” (pg. 9).

Star Trek had the capability to “share and disseminate viewpoints alternative to dominant narratives” (Stack & Kelly, 2006, p.9). As a network TV show, it could reach thousands of people and it had the potential to influence a new way of thinking that went against societal norms at that time, and to encourage change, particularly when it came to race and gender roles. Creator Gene Roddenberry’s liberalist-humanist views intended to present a Utopian future society where issues of racism, gender equality and war would no longer exist. But at the same time representations worked to undermine that ideal.

Roddenberry wanted, “to develop a show that was intellectually stimulating and addressed social issues.” (Johnson 2005, p.72). However, there is a contradiction between representations and narratives: although this is supposed to be a utopian society without those issues, in reality the show presents a world which is male dominated, where women are portrayed largely as sex objects and although racism doesn’t seem to exist among humans, there is still racism between species such as humans, Romulins and Klingons. The counter narrative is that in the “real world” during the time period of the show (late 1960’s), racism still existed in society. It was a divisive issue with strong opinions on both sides. In addition, the network wielded power over the show, at times overriding Roddenberry’s idealistic views which they sometimes saw as controversial.

In the episode, “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” a narrative of anti-racism is conveyed. The Enterprise picks up the last two survivors of a war-torn planet who are still intent on destroying each other. The half-black, half-white aliens hate each other because they are oppositely coloured. The two continue to escalate fighting until the Enterprise reaches their home planet, only to find that the planet has been destroyed due to intense racial hatred. Instead of learning from the tragedy, the two begin to blame each other for the planet’s destruction and continue to fight. Critics viewed this representation of racism as being heavy-handed, although fans of the show felt it was one of the best episodes due to its message.

On the one hand, the series provided social commentary of anti-racism (see above) or presenting “the United Federation of Planets.” At that time television was dominated by the depiction of white people and Star Trek went against that by including multi-racial characters such as Uhura and Sulu. The counter narrative to this is that they are portrayed as non-essential and in the background, compared to white male hero, Captain Kirk.

Bernardi (1997) states:

Contrary to what is commonly said about this science fiction series, … Star Trek’s liberal-humanist is exceedingly inconsistent and at times disturbingly contradictory, often participating in and facilitating racist practice in attempting to imagine what Gene Roddenberry called, “infinite diversity in infinite combinations. (p. 211)

In relation to ideology, through creation of a complete universe with its own morals, technology and culture, science fiction texts such as this are more likely to be viewed as realist texts.

Therefore, with such a close relationship to realism, the writers of Star Trek could infiltrate contemporary concerns of its production time, such as civil rights and the Cold War, into its diegesis (Gregory 2000, p.25; Bernardi 1997, p.214)

In conclusion, although creator Gene Roddenberry’s intention was to create a cerebral show with the potential to influence social change, some of the representations were in fact counter narratives to that.

References:

Bernardi, D. (1997) Star Trek in the 1960s: Liberal-Humanism and the Production of Race in Science Fiction Studies , 24 (2): 209-225.

Gregory, C. (2000) Star Trek: Parallel Narratives. New York: St. Martin’s Press. (p. 25)

Johnson, C. (2005) Telefantasy. London: British Film Institute Publishing. (p. 72)

Stack, M., & Kelley, D.M. (2006) Popular media, education and resistance. . Popular media, education, and resistance. Canadian Journal of Education , 29(1), 5-26.

Disney Princess: Enchanted Journey is a video game of the Disney Princess franchise, which was released for the Wii in 2007. Targeted at kindergarten-aged girls, the game centers on a girl whose quest is to help restore a run-down castle by helping five princesses —Snow White from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Ariel (The Little Mermaid), Belle from Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin’s Jasmine, and Cinderella in their struggle against an evil witch and her “Bogs.”

At first glance this game has a feminist narrative in that in contrast to the Disney Princess story lines, the various Princesses are not rescued by princes; they go on their own adventures and move through various stories, responsible for their own accomplishments. The counter narrative is that the Princesses are represented as being pretty, concerned with appearance and goal-oriented towards “decorating and making the castle beautiful,” or adorning themselves with beautiful dresses and jewels. This positions females as being inferior to males, concerned with superficial things such as clothing and décor, versus more substantial accomplishments. Their power is the use of a magic wand, which infers they do not have real power and their accomplishments are not as a result of intelligence or skill, but something beyond their control. They turn “Bogs” (evil minions) into butterflies, rather than fighting or killing them, which would be a typical action in a male-oriented game. After progressing through levels which involve five Disney Princesses, the final battle is against Zara – an evil ex-Princess whose goal is to “stop every girl from becoming a Princess.” Looking at this from the perspective of a feminist lense I have to ask, “Is this the highest goal a girl can strive for?”

This game (and related merchandise), anticipates girls’ identities and embodies social roles for them as being lesser than boys, by having them “flick a magic wand” to solve problems, rather than using reason, and immersing them in the idea that appearance is everything. The Disney Princess product line influence girls to undertake a discourse of expected roles and behaviour with limited potential and significant social limitations. According to Wohlwend (2008), this happens through modelling of:

“particular ways of talking, speaking, dressing, playing, and so on, that index affiliation with a larger group or set of beliefs. Because these ways simultaneously index a group’s beliefs and tacit rules, I also use discourse in a Foucauldian sense to indicate how language circulates power in global and local ways…, (p.58)

So while girls may wish to overcome social limitations and predetermined gender roles, they are also torn to re-enact the story lines and behaviour they are bombarded with on many levels. The invasive nature of the media and in particular, marketing have a subliminal effect on gender roles and the self-image of girls:Steyer and Guggenheim (2017) state that:

“Decades of research, outlined in this report, demonstrate the power of media to shape

how children learn about gender, including how boys and girls look, think, and behave.

Depictions of gender roles in the media affect kids at all stages of their development,

from preschool all the way through high school and beyond. These media messages

shape our children’s sense of self, of their and others’ value, of how relationships should

work, and of career aspirations.

Tragically, that influence has served to perpetuate notions that boys have more value

than girls. Gender stereotypes riddle our movies, TV shows, online videos, games, and

more, telling our boys that it’s OK to use aggression to solve problems and our girls that

their self-worth is tied to their appearance. These images are so deeply ingrained and

pervasive that many of us don’t even notice the bias, making it more insidious because

we don’t even realize we’re exposing our children to it.” (Introduction)

Here is an advertising trailer for the game:

Trailer Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEVVXsHHCIA

In terms of a critical lense, it would appear that this game is geared towards girls: only girls appear in the advertising materials, playing the game and having “fun.” The text displayed in the commercial reads, “Enter a World of Magic Where Dreams Come True.” “Create and Dress Up Your Character” and “Awaken the Princess in You.” The key message is clear, “It’s fun to be a Princess!” The marketing materials feature images of the princesses in their fancy gowns and many of the associated products for sale in store are available in pink and/or purple, traditionally “female” colours.

This game ties in to Disney marketing through merchandise sales of a variety of Princess items including costumes, clothing, school supplies, CDs and DVDs. These items are sold through a variety of product lines including “Disney Princesses” (all five together), and each individual Princess which can appeal to a variety of girls due to their different hair colour. Jasmine is the only Princess who represents a non-white ethnicity, which when viewed with a cultural lense skews this product in its emphasis of the portrayal of Caucasians as a beauty ideal. Many young girls aspire to the looks, dress and behavior of these princesses, seeing them as an ideal in beauty and behaviour.

Buckingham (2011) writes, “According to Bauman, consumption has now become central to people’s lives; it is the condition of their identity, their very reason for being. The power of consumerism is inescapeable and all encompassing…” (p. 29)

The pervasiveness of the stereotypical Disney Princess discourses perpetuated by consumerism can create limiting social expectations for girls. Since young girls may be exposed to this game and other Disney Princess discourses, they may grow up upholding a subservient gender role to boys. This can influence their behaviour in social situations, unless this is challenged by those around them, or they themselves learn to use a critical lense, ultimately transforming their gender and societal roles.

References:

K. Wohlwend (2008) Damsels in Discourse: Girls Consuming and Producing Identity Texts Through Disney Princess Play

Indiana University, Bloomington, USA

Retrieved from: http://www.seriousplaylab.com/pop/princess_play.pdf

James P. Steyer and Amy Gugeinheim Shekan (2017)

Watching Gender: How Stereotypes in Movies and on TV Impact Kids’ Development

Retrieved from: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/pdfs/2017_commonsense_watchinggender_executivesummary_0620_1.pdf

Buckingham, D. (2011) Understanding Consumption in The Material Child: Growing up in Consumer Culture.. London: Polity Press.